One of the most common nerve conditions that I treat is the painful neuroma. These are some of the most challenging issues to treat, requiring a very careful eye for diagnosis AND a thoughtful approach to treatment.

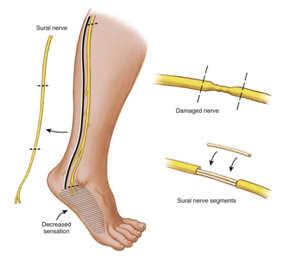

Normally, nerves are smooth and flowing structures (Figure A). Neuromas form after a nerve has been cut/injured* (Figure B) - by default, the body's default response to this is the prepare the near-end of the nerve to regenerate: it automatically tries to find the far-end of the nerve. If the environment won't allow the near-end to find the far-end (either because the gap is too much to overcome or due to lots of scarring around the injury), nerve regeneration will not occur (Figure C). The near-end is constantly seeking the far-end and remains in an inflammatory state, leaving it very irritable and causing pain. The near-end of the nerve can be rubbed on by the moving skin and fascia, creating remarkable sensitivity that is unbearable. This is the type of pain that patients often describe as sharp, shooting, shearing, "ice pick" or stabbing, starting at the area of nerve injury and heading/radiating to somewhere further out on the arm/hand or leg/foot.

*"neuromas-in-continuity" can appear with long-standing compression of a nerve or with scarring of a repaired nerve

Now we are left with a tough situation in which a nerve is trying to regenerate but is instead causing pain. So what can we do about it? Most nerve surgeons will provide the response that the best treatment is prevention of nerve injuries. YES, THIS IS ABSOLUTELY TRUE... but not helpful for the patient who is already suffering from a nerve injury.

For those patients with painful neuromas, we can try a few different options. In my experience, if we can isolate the patient's symptoms to a specific portion of the nerve that is inflamed, we can target our treatment to this area. I typically send my patients for ultrasound-guided injections to the suspected painful neuroma region, and if this provides even temporary and/or partial relief, this is a good sign that I can help the patient with surgery. If I am having a hard time localizing the patient's symptoms to one specific nerve, I will typically start with medications for nerve pain (such as gabapentin, pregabalin, nortryptyline, amitryptyline, or duloxetine).

For those patients who respond well (or even somewhat well) to an injection, I recommend surgical treatment of the neuroma. The near-end of the nerve is trying to regenerate, so I prefer to target our treatments to help it find the far-end. In surgery, we freshen the near and far ends of the nerve, then place a nerve graft (sometimes autograft, such as from the sural nerve... and sometimes allograft from a cadaver) to lay the "train tracks" for the nerve to regenerate (Figure D). If I cannot do that reliably, I will take the near-end of the nerve and bury it in muscle - while the nerve will not regenerate, it will at least find a "dead-end" in the muscle, where it will not be irritated by constant contact from the skin (Figure E). In both of these situations, my goal is to RELIEVE PAIN... and I counsel all patients that they are almost certainly trading off their pain but getting some numbness in return.

Painful neuromas are a very challenging problem, but I have also found patients with this issue to be some of the most grateful patients I have. Careful diagnosis, thoughtful treatment, and appropriate counseling about expectations are the key to helping patients with this condition.

Christopher J. Dy, MD MPH

My Bio at Washington University Orthopedics