I wanted to write something about sural nerve harvest because it is something I discuss with patients nearly every time we are talking about treatment of nerve injuries. We will often use the sural nerve as an autograft during nerve reconstruction cases. After we remove the scarred/injured part of the nerve, there is usually a gap that we cannot repair directly. We will suture the sural nerve graft to bridge the gap between the nerve ends, often laying down multiple segments of the graft ("cabling" the graft) to replicate the thickness of the nerve we are replacing.

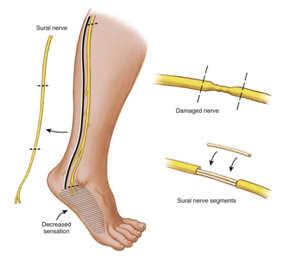

I wanted to write something about sural nerve harvest because it is something I discuss with patients nearly every time we are talking about treatment of nerve injuries. We will often use the sural nerve as an autograft during nerve reconstruction cases. After we remove the scarred/injured part of the nerve, there is usually a gap that we cannot repair directly. We will suture the sural nerve graft to bridge the gap between the nerve ends, often laying down multiple segments of the graft ("cabling" the graft) to replicate the thickness of the nerve we are replacing.How is the sural nerve harvested? The nerve is identified through either one long incision or a series of small incisions along the back of the calf (just behind the smaller bone in the shin - the fibula). The nerve is identified near the ankle level and traced up to the knee level. After the sural nerve is cleared from the surrounding tissue, the nerve is cut, removed from the body, and prepared for grafting.

What are the downsides of harvesting the sural nerve? Like they say, there's no free lunch.

- Numbness: The sural nerve's normal function is to provide sensation to the back of the calf and the outer border of the foot (area seen in purple). Removing the sural nerve will lead to numbness in this area, which is most noticed when walking barefoot or in sandals, or when playing sports like soccer/football that require contact with the outside of the foot. All patients will almost certainly experience this.

- Pain: Anytime a nerve is cut (including for a harvest), the nerve ends are very sensitive since they are trying to regenerate. Most of the time, the near-end of the nerve retracts into the calf muscles and doesn't see much irritation since it is buried so deeply. But in some patients (about 5%), the nerve can be very sensitive (painful neuroma). Most of the time, this will get better over time (about 3-6 months). Medications for nerve pain may be helpful. Very rarely, another surgery is needed to re-cut the nerve ends and bury them deep in muscle or bone.

- Infection, hematoma, wound healing problems, and blood clots (deep venous thrombosis) - these can happen in any leg surgery and certainly need to be mentioned.

Are there any other options? Nerve grafts can be harvested from other sources (such as the saphenous nerve in the thigh, the medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve around the elbow, and the posterior interosseous nerve in the wrist) instead of (or in addition to) the sural nerve. The sural nerve tends to be many surgeons' preferred choice (including mine) because it has the highest percentage of nerve fibers (fascicles), a lot of graft can be harvested (up to 35-40cm), and the downsides seem to be tolerated well. Cadaver nerve graft (allograft) is another option, but the studies are still being done to show if it is "good enough" when compared to using the patient's own nerve (autograft). One of the biggest issues with the allograft is that the process to make the allograft non-reactive and non-infectious removes some of the cells that promote nerve regeneration (Schwann cells).

Christopher J. Dy, MD MPH

My Bio at Washington University Orthopedics